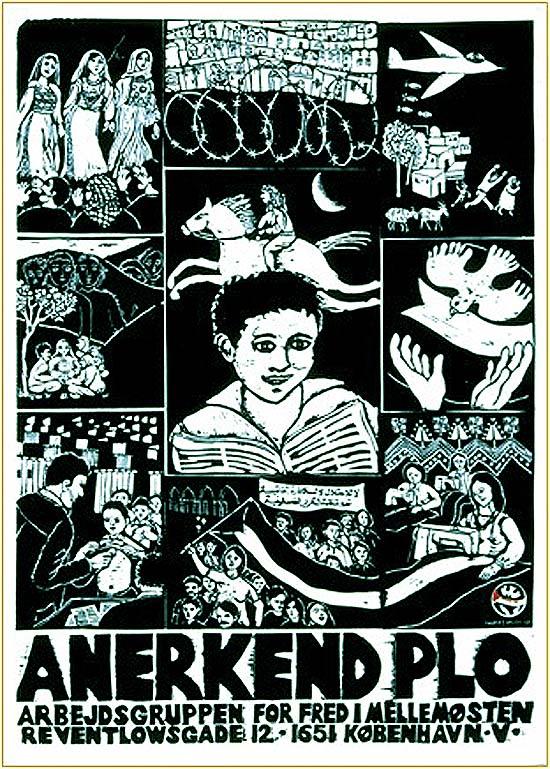

Danish translation: Recognize the PLO

This is a narrative poster detailing modern Palestinian history as seen from the perspective of a child living in a refugee camp. It is a block print created by the artist Thomas Kruse who was a member of Rode Mor (Danish: Red Mother), an anti-imperialist arts collective that flourished in Denmark from 1969 to 1978.

The poster’s caption, “Anerkend PLO,” translates from Danish as “Recognize the PLO” and refers to a major political objective of the Palestinian revolutionary movement: to have the United States and Israel recognize the Palestine Liberation Organization as the sole, legitimate representative of the Palestinian people. It seems difficult to believe now, but from its inception in 1965 up until the Oslo Peace Accords were signed in 1993, both the U.S. and Israel were engaged in almost constant effort to prevent the international community from recognizing the PLO. Ninety-four countries, not including the U.S. or Israel, formally recognized the state of Palestine and established diplomatic ties when the PLO unilaterally declared its existence in 1988. The current Bush administration holds out the possibility of recognizing a Palestinian state within five years under the provisions of its “road map” for Middle East peace.

In the central frame, a boy is reading a book. In his imagination, an armed Palestinian feda’ee (Arabic: commando) rides across the sky on a white horse. The story the boy is reading is the one that borders the poster, and he is the man on the horse.

It also is likely that this poster quotes the prophet Mohammed’s legendary journey from Mecca to Jerusalem on a white horse name Al Burak. The crescent moon, a symbol of Islam, lends support to this interpretation.

In modern Palestinian culture, the white horse is a symbol of the revolution and in this poster it has everything to do with the boy’s dreams of one day escaping the squalor of the camps and returning home to a restored Palestine.

The frames are read counterclockwise from upper right to left, echoing the right-to-left direction of Arabic script. The first frame shows an Israeli military aircraft dropping bombs on a Palestinian village as the townspeople flee. The top middle frame depicts the next phase of life for those Palestinians who became homeless in 1948: a cramped refugee camp surrounded by barbed wire.

The next frame in the upper left hand corner shows Palestinian women in handmade dresses featuring intricate tatreez (Arabic: embroidery) performing a traditional dance, likely organized by a cultural committee of the camps. This frame is meant to show that though the refugees are dispossessed, they are neither demoralized nor defeated.

The next frame shows a Palestinian woman reading aloud to her family the history of their people. Stepping out of the surrounding hills are mystical images of other Palestinians, perhaps from past generations or from the generations of those not yet born. For American viewers of the poster, this frame brings to mind the haunting and eloquent “1854 Treaty Speech of Chief Seattle”:

...And when the last Red Man shall have perished, and the memory of my tribe shall have become a myth among the White Men, these shores will swarm with the invisible dead of my tribe, and when your children’s children think themselves alone in the field, the store, the shop, upon the highway, or in the silence of the pathless woods, they will not be alone. In all the earth there is no place dedicated to solitude. At night when the streets of your cities and villages are silent and you think them deserted, they will throng with the returning hosts that once filled them and still love this beautiful land. The White Man will never be alone.

Let him be just and deal kindly with my people, for the dead are not powerless.

Dead, did I say? There is no death, only a change of worlds.

The next frame shows a doctor visiting a refugee camp and a long line of children waiting for their medical exams. This reference is meant to highlight the practical benefits that the PLO delivers to the residents of the camps such as health services, schools, cultural activities, vocational training, etc. It shows why the PLO has the widespread support of the Palestinian people.

The bottom middle and lower right hand corner images work together. They show women from a PLO-sponsored vocational workshop who have learned to sew and who have created a Palestinian flag (outlawed by Israel up until 1993) marching at a rally. The banner they carry reads “No to Occupation! No to the Civil Administration! Yes to the Palestine Liberation Organization!” This slogan reflects the political struggle of the time (1978), with the PLO on the one hand determined to win world recognition of its role as the interlocutor for the Palestinians, and Israel and the U.S. on the other, seeking to prevent that from happening.

The final frame shows a dove flying over the Palestinian flag and coming to rest in the hands of a refugee. The soldier on the white horse has returned to his liberated homeland in the form of this bird of peace. This image graphically evokes the political belief that peace will come with the realization of the goal of Palestinian national self-determination.

Kruse applies two ancient Scandinavian art forms — the wood block print and the tradition of the heroic narrative — to tell the modern story of the Palestinians, a people far removed geographically, politically, and culturally from Denmark. By doing so, Kruse enriches the content of Danish graphic culture while also contributing to the phenomenal visual and iconic diversity of the twentieth century’s most enduring political art genre, the Palestine solidarity poster.