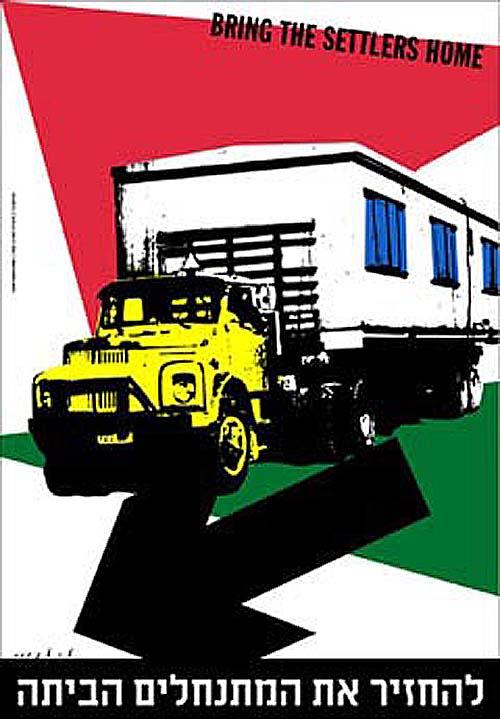

This poster addresses one of the most important aspects of the Palestinian-Israeli conflict, and one least understood by the American public: mainstream Israeli opposition to the construction and expansion of Jewish settlements in the Occupied Territories.

The central graphic element is a bright yellow truck hauling out of the Occupied Territories a mobile home trailer painted in the Israeli national colors, blue and white. The truck and trailer are graphically reminiscent of the prairie schooners favored by American pioneers who swarmed into the U.S.’s newly opened Indian Territories during the Westward Expansion movement, especially after the signing of the Homestead Act in 1862. The preferred direction for the truck is made perfectly clear by the enormous arrow that takes up the bottom third of the poster. The large red, green, and white triangles in the background, together with the black arrow, make up the colors of the Palestinian national flag.

The sharp triangles also suggest that the presence of Israeli settlers has fractured Palestinian life (a position shared by many, including the U.S. State Department) and that even after the settlers depart, Israel will bear a moral responsibility for reconstruction there.

Bring the Settlers Home was created in 1980, during Menachem Begin’s tenure as Israel’s Prime Minister (1977- 1983), when settlement expansion was forging ahead at full throttle under then-Minister of Agriculture and chairman of the ministerial committee for settlements, Ariel Sharon. It demonstrates that the Israeli left foresaw the inevitable crisis that would result from Israel’s misguided settlement policies long before any of the various Israeli parties, coalitions, or governments.

The caption, “Bring the Settlers Home,” demonstrates that as far back as 1980 many Israelis did not consider the West Bank (“Judea and Samaria” in settler-speak) part of the Israeli homeland. That feeling remains strong today. A recent poll (June 2003) conducted by the Israeli newspaper Ma’ariv, found: 56 percent favored closing illegal outposts erected after March 2001, as the U.S.-backed “road map to peace” requires; 59 percent backed freezing settlement expansion; 62 percent agreed that the Israeli occupation of the Palestinian territories should end; and 57 percent said the Palestinians should have their own state.

With this poster Tartakover has countered Menachem Begin’s famous claim to be creating “facts on the ground” by demonstrating that those “facts” can be moved: the settlements can be dismantled in exactly the same way they were established, by putting wheel carriages on all the moveable property and towing it back to Israel — back home.

But Tartakover is not really talking about returning property: he is talking about people. The Israelis who choose to settle in the West Bank and Gaza are not the Israeli counterparts of the Quakers — peaceable, unarmed, live-and-let-live types who want nothing more than to farm and work in cooperation with their neighbors. Rather, the settler movement is (for the most part — see also New) ultra-religious, heavily armed, bellicose, and dedicated to the biblical notion of a “Greater Israel.” Ideologically driven as they are, they see the indigenous Palestinian population of the West Bank and Gaza as interlopers without any claim to the lands the settlers consider part of an ancient Jewish kingdom that they intend to resurrect. They consider the mass, forced expulsion of the Palestinian population from the West Bank — “transfer” in settler-speak —as a real and appropriate option.

During the American Civil War (1861-1865), the Confederacy was much smaller in terms of population compared to the North, agriculturally-oriented, and grossly inferior in terms of manufacturing capacity. Yet it won victory after victory in the first phase of the war. The South, a religiously devout region, interpreted this string of triumphs as proof that God was on its side. Later in the war, when the South was losing most of its battles and defeat was inevitable, Southerners felt trapped because there was no way left open for them to explain their situation except that God had turned against them.

The ultra-religious right in Israel believes that Israel won the Six Day War (1967), which it fought simultaneously against Egypt, Syria and Jordan, because God was on their side. The capture of Jerusalem with all its religious significance for Judaism helped to fuel this interpretation not only among religious Israelis but in the secular community as well. That victory, however, contained the seeds of many of Israel’s worst crises: the humiliating and utterly fruitless bloody nose Israel suffered at the battle of Al Karameh in 1968; its disastrous invasion and 20-year long occupation of Lebanon; its increasing isolation in the U.N. and the loss of support in the international community in general; the deterioration of its relationship with the U.S.; and the worsening situation in the Occupied Territories. Moreover, these problems have created new divisions within Israel’s body politic. All of these draining crises stem directly from Israel’s victory in the 1967 war, as does its phenomenally expensive and controversial new “security fence” aimed at protecting Israel proper and the Jewish settlements in the West Bank from infiltration by Palestinian militants.

Israeli artists have been voicing their opposition to the Israeli presence in the Occupied Territories for more than twenty-five years, yet few politicians in Israel have the courage to stand up to the ultra-nationalist parties: the Gush Emunim (Hebrew: Bloc of the Faithful), Tsomet (Crossroads), Kach (Thus), Kahane Chai (Kahane Lives), Moledet (Homeland), Herut (Freedom), and the National Religious Party that together form an ideological phalanx with which few Americans, and increasingly few Israelis, have much in common. These ultra-nationalist parties constitute only a small percentage of the population of Israel, however, their power is magnified owing to the nature of the country’s parliamentary politics.

Though Tartakover created this poster in 1980 in response to the religious right’s obsessive determination to colonize territory that the entire international community considers to be Palestinian, its message is no less urgent, and no less ignored, by Israel’s leaders almost a quarter of a century later.