Bulldozer rules

“George Orwell in his wildest dreams could not have imagined this.”

—Ezra, Israeli plumber and social activist

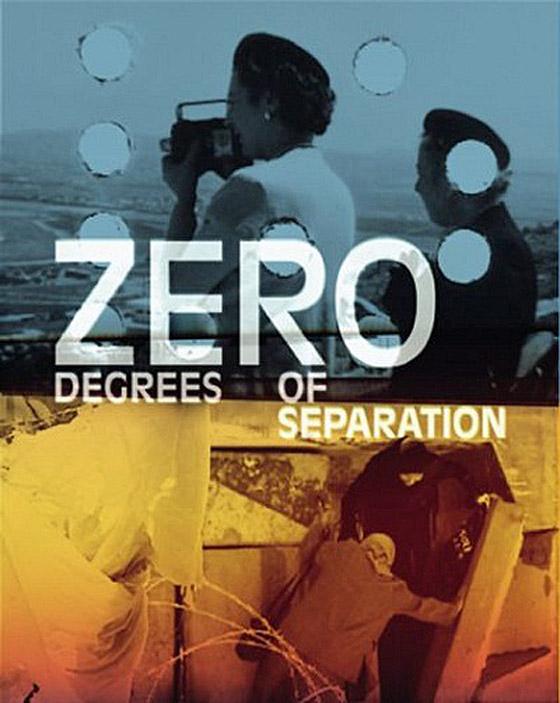

In Zero Degrees of Separation, Elle Flanders has crafted a film that goes far beyond its subject matter, providing the thoughtful viewer with a bleak testament to the primary failings of the human condition: an unquenchable lust for power over others and a dearth of unconditional love between couples—no matter which orientation.

The narrative ingredients include silent home movies from Flanders’ grandparents shot during the rise of Zionism and two Israeli/Palestinian gay couples (Ezra & Selim, Edit & Samira) who struggle to live their lives together in modern day “Independent” Israel. It turns out that Ezra used to tend Flanders’ garden when she was growing up as a child, but that coincidence is more curious than intriguing.

Those components are woven into a rich visual and aural fabric through captions and statistics (further reinforcing the era before widespread availability of “talkies”) and David Wall’s score. The music varies from stilted, student-in-training piano lines, to effective mallet and drum soundscapes; the stellar muted-trumpet interventions immediately kindle recollections of Copland’s Quiet City. But the action is miles from soothing.

Longtime resident and plumber with a social conscience, Ezra delights in taking on mindless authority at every turn (“We just follow orders” says a young soldier with a blindfolded Arab sitting stoically on the back seat of the army vehicle). He dispenses New Year’s cards and sarcasm to Israeli soldiers, nearly begging them for a fight. His much junior lover, Selim, is an illegal. Under house arrest for the crime of being a Palestinian without the proper papers, the frequently-jailed, ruggedly-attractive man takes his plight in stride. “You go with the flow.” Soon enough, he’s deported, ending a five-year relationship that couldn’t flower beyond its borders.

Initially, the lesbians manage to compromise through their cultural/heritage differences. Edit came to Israel because her Argentinean parents were on a hit list so chose to escape tyranny and relocate to the land of dreams. On Independence Day Edit parties with friends while her partner marks Nukba (The Catastrophe) by staying home and listening to the music of Fairouz. Both work in the service of humanity (Edit, a social worker at the Rape Crisis Centre, Samira an oncology nurse) and spend their off hours protesting injustice. Yet their time together also comes to an end, unable to sustain themselves or those around them who suffer the ravages of violence against women and the endless cycle of suicide bombers and reprisals.

No one, it seems, can get along.

The numbing facts ($25 million per month was spent by Israel in 2002 on protection services for its settlements; the “separation fence”—a.k.a. “security fence,” “anti-terrorist fence,” “Racial segregation wall”—between Israel and the West Bank is, in places, twice the height of the Berlin wall and cost $3.4 billion) and innocent faces seem to point to the need for a huge bloodbath or revolution if lasting peace is ever to come to the region.

The most compelling imagery comes from Flanders’ family vault where the Ashkenazi Jews—replete in trendy suits, pumps and stylish dresses—look completely out of place in the arid desert whose indigenous population had subsisted for centuries before power-hungry leaders from many countries decided to employ their own people and bring the horrors of progress to the Holy Land. Little wonder everyone smokes.

Ezra says it all: “There are no saints in this story.” Source:http://www.jamesweggreview.org/Articles.aspx?ID=380